Babygirl and the Myth of the Girlboss

The figure of the girlboss may haunt our discourse, but it's the hot mess heroine who is the real 21st century feminist icon

As CEO of her robotics company, Romy works hard to project toughness even though her signature high-necked dress shirts appear to be strangling her. She moves through her office unsmiling, her hair pulled tightly into an updo that looks severe even though she has clearly taken pains to soften the look with strategically placed curls. In her home life, she also plays the role of manager, organizing parties and holiday photo shoots. In most aspects of her life, Romy likes to be the one in control. As the film explores, her desires in the bedroom are quite the opposite.

This isn’t a new kind of female character.

The past decade has ushered in an array of heroines who yearn to escape societal expectations and pressures. Shows like Fleabag, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, Mrs. Fletcher, and Chewing Gum feature female protagonists who are blunt about their desires and eager to understand their own chaotic inner worlds. My first thought when I saw the sex scenes between Romy and her intern Samuel was how much the film echoes the kind of sex found in the TV show Girls, even though on the surface, Romy and Hannah could not be more different. Both characters fumble through kinky relationships, confused about how their desires motivate them. And both characters are unable to advocate for what they need because they aren’t sure what they actually want.

This “hot mess heroine” archetype is one of the most iconic in 21st century feminist storytelling, but you wouldn’t know it based on the current obsession with the death of the girlboss. The disdain for the supposed feminist icon is found everywhere, from male viewers who express frustration at the existence of She Hulk, to younger feminists who complain that the girlboss is more about buying into the patriarchy than pushing back against it.

Though there is an entire mythology built around her demise, the social and political impact of the girlboss isn’t nearly as substantial as her critics claim. In fact, I would argue the girlboss isn’t a true pop culture icon at all, but a loose stereotype based entirely on marketing and vibes. The neologism entered the vernacular in 2014 after the publication of the book #Girlboss by Sophia Amoruso, which sold well, but was also immensely polarizing, with many feminists in particular dismissing the term “girlboss” as problematic.

To claim the girlboss is dead is to claim that she was once a beloved icon. The truth is that not only has the term always been criticized, but that there has always been considerable backlash against pop culture representations of working women, who are often portrayed as vapid, selfish, angry, deluded, or just incredibly mean. In contrast, it’s the stories that grapple with female desire in all its messiness that have been most critically revered.

Which brings me back to Romy and my conviction that she is a standard “hot mess heroine.” The heart of the film is that Romy’s barely hidden vulnerability is her true self and that all that bravado is just a mask. One moment in particular highlighted this for me: when Romy puts a blanket over her head and tremulously asks her husband of nearly 20 years to dominate her, even though she knows that he will likely refuse. That’s the Romy that the film is about: a woman who is delicate as a fawn. Later in the film when Romy barks back at a man who attempts to blackmail her, we simply see the mask come back, rather than a full integration of her distinct parts.

It's Romy’s lack of curiosity at her own inner workings that renders the exploration of female sexuality throughout Babygirl oddly tepid. We get a brief mention of Romy being raised in a cult, but there is too little backstory to truly flesh out who she is as a character. The film’s best scenes portray the careful sexual negotiation between Romy and Samuel. These scenes are fascinating to watch, equal parts funny and tender, but they also aren’t quite as lusty as the ad campaign for Babygirl wants you to think they will be. Romy and Samuel’s negotiations in the bedroom always feel a bit stilted and the only scene that seems overwhelmingly ecstatic takes place in a nightclub where Romy is swept up in the excitement and energy of allowing herself to strip off her blazer and dance.

“This Christmas get exactly what you want” the posters of Babygirl coo over a still of Romy looking up at Sam. The question of what women want is often presented like a mystery to be solved, but the idea that adult women have never thought about their desires before the advent of a film like Babygirl would be laughable if it weren’t so infantilizing. Every few years we get a new book or film or TV show about female desire that takes center stage. This façade of newness is, I suppose, necessary for the marketing machine to continue to churn out new content that we lap up like Romy drinking a saucer of milk. But it also flattens conversations about female desire, relegating the discourse to a kind of fashion trend.

The same thing happens when we take paper-thin stereotype of the girlboss and pretend that she is some kind of exalted icon that needs to be torn down. The supposed shift in how women are thinking about ambition strikes me as particularly sinister in a cultural and political moment that is intent on claiming that women who are ambitious are miserable. Perhaps this is also why Babygirl is a disappointment—it lures viewers in with the promise of a new idea and is only able to offer up a story we’ve already seen.

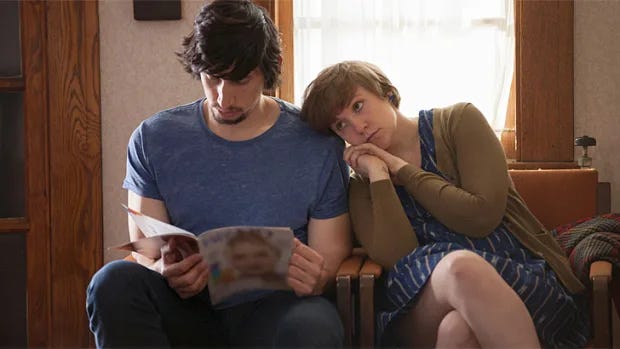

I love the classic Hollywood BS of this image of her looking up to him, "Oh, white man, please educate me!"