In Defense of Artifice

On Wes Anderson and the unexplainable side of style

Two things happen when a new Wes Anderson movie arrives in theaters, as The Phoenician Scheme, Anderson’s twelfth film, did last month.

First, I get excited. I like Anderson’s movies.

Second, I get frustrated. In reviews and in conversations about the movie, I come across the descriptor that will surely forever follow the director: Quirky.

Quirky is, perhaps, the adjective I despise the most. Even when it’s meant as a compliment, it reads as dismissive. It’s a sign of a surface-level interpretation, of disengagement in the face of deeper understanding; an allergic reaction to style.

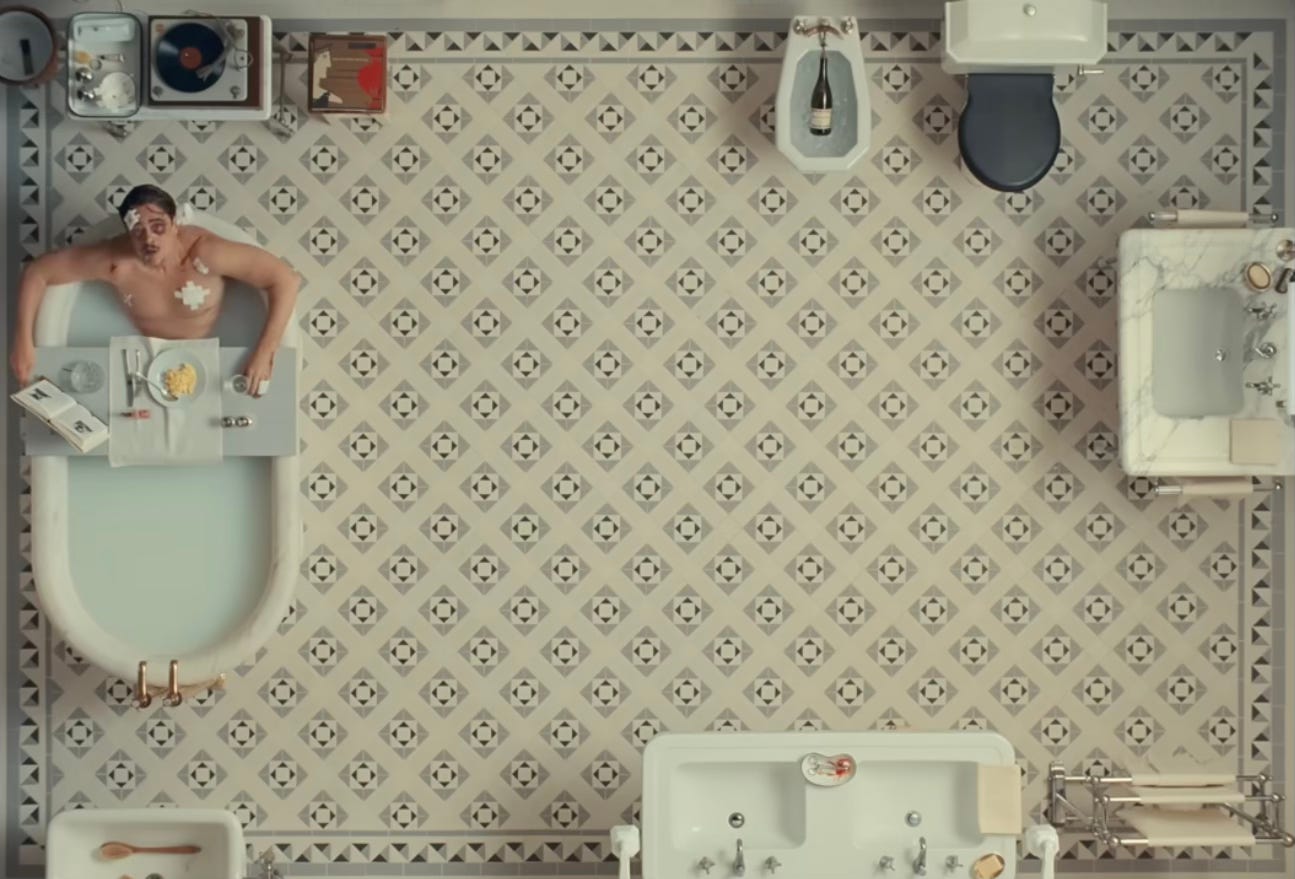

I understand why Anderson’s movies are described this way. They have a distinctive look and feel—precise framing, Brechtian line delivery, meticulous costuming, precious-looking props. The movies tend to be comedies, or at least they have jokes and funny dialogue. Quirky seems like an appropriate word to describe the films’ erratic peculiarity. But “quirky” implies that peculiarity is all there is. With Anderson’s movies, beneath the squared shots and the precisely written lines delivered with flat affect, are ideas and performances that demand deeper attention.

Take The Phoenician Scheme. One of the lead characters is grappling with visions of his death and the other is an aspiring nun whose descriptions of her beliefs come in short lines that emphasize the beauty of faith, even in the face of doubt or uncertainty toward organized religion. Global power moves between schemers, syndicates, criminals, and governments. No organization is to be trusted. Every person is more than they seem.

Or Rushmore, a movie about an adolescent whose discomfort with his social station and profound loneliness lead him to fill his need for adult role models by play-acting as an adult himself.

In “Asteroid City” a nesting-doll structure (the movie is presented as a television show about the production of a play) underlines the value of artifice in grappling with complicated emotions.

But the style becomes the legacy. The Life Aquatic is an achingly sad movie that’s now largely remembered for the reddish-orange watch caps the characters wear.

It was with The Life Aquatic, released in 2004, that the reputation for quirk took hold. It was Anderson’s fourth movie. The prior three (Bottle Rocket, Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums) were certainly stylish, but the largely negative reviews of The Life Aquatic argued that style had overtaken substance as the motivating force in Anderson’s work. Roger Ebert used the phrase “terminal whimsy” to describe it. Anthony Lane wrote in The New Yorker that “we have grown accustomed to the unassailable claims of deadpan, although Anderson’s detractors might argue that underreaction, having begun as a show of hipness, has now frozen into a mannerism. What chance remains, they would ask, for the venting of genuine feeling? What would it take to harry these controlled characters into grief, or the silliness of bliss, or unconsidered rage?” Even the action scenes of that movie, Lane writes, were “lightly held within quotation marks.”

2004 was perhaps the worst year the movie could’ve come out. It was the year of Garden State and Napoleon Dynamite, two movies awash in quirk that were immediately tied to the idea of Millennial Hipsterdom—the twee side of what would retroactively (and inaccurately) be called “indie sleaze.” Their aesthetic was a fad to grow out of. In Garden State, Natalie Portman’s character says that when she feels down, she makes a sound or does a motion no one has done before, just to feel unique. Meaningless noise is quirky. Portman’s character—an archetypical “Manic Pixie Dream Girl”—says she does this to feel original, “even if it’s only for a second.” That’s how long quirk lasts.

Seen now, after eight more films from Anderson, The Life Aquatic does indeed mark a shift in the director’s career. It moved the action away from the roadside motel of Bottle Rocket, the private school of Rushmore, and the ‘70s-movie inspired New York of The Royal Tenenbaums and into a fictitious Mediterranean filled with elaborate boat sets, pirates, and abandoned island hotels. At the time, this is what read as a retreat into comfortable style—a decision to separate from reality and set every movie (with the exception of The Darjeeling Limited) in a snow globe. From the seascapes of The Life Aquatic, Anderson moved to the imagined island of New Penzance in Moonrise Kingdom, the fake European countries of The Grand Budapest Hotel, the 1950s southwest of “Asteroid City”, and the imagined Phoenicia of this year’s release. This is the world seen in the myriad parodies, the tributes on social media, and in the pandemic-era meme. It’s behind both the loving homages and the sneering dismissals.

Anderson’s style is not purely for aesthetics, and his alternate worlds aren’t built only to escape the intrusions of technology like cell phones. Anderson’s worlds are fun-house mirrors more than snow globes. They are precious because they depict ideas that are fragile—childhood, beauty, wonder. The world is constantly at risk of being smashed. Like the actors in “Asteroid City” or the writers in The French Dispatch, the work of creation (a play, a performance, an article) is simultaneously a way of understanding the world and a defense against the inevitability of its destruction.

When asked about the memes his work has inspired, Anderson told Mashable, “if it's somebody who's imitating me [and my work], but making the people just stoic, dead expression…I don't feel that's what I do. I wouldn't print [that] take, right?" His confusion is the difference between thinking about a work and simply looking at it.

The pitfall of developing a signature voice is that people will recognize it. Once they do, they stop looking for anything else. They watch, read, or listen in hopes of finding a way to feel smarter than the work—even if they ostensibly enjoy it. This is how recognizable themes become “obvious,” how a logical plot becomes “formulaic,” how a style becomes a copyable meme. It’s how difference becomes “quirk.”

There is no winning with this audience. The way to stop their self-confidence is to make something beyond their understanding, which then becomes inscrutable, dense, or “weird.”

As a description of art, “weird” is a bizarro cousin to “quirky.” Both are dismissive. Weird describes what the viewer determines is unexplainable. To say something is weird is to say it has a strangeness that’s beyond understanding. To call something quirky is to say you understand it all too well. Weird says “I don’t want to engage with this.” Quirky says “I don’t have to.”

When faced with artifice, with a recognizable style, with a distinctive voice, or even with a charlatan’s pose…instead of dismissing it, ask why. Why is it like this? What appears to be quirk is, often, a style that makes it possible to deliver a message. It’s the language an artist develops to say something they have to say but may not want to say it in a straightforward way.

Some artists are raw. Rawness has power. Elliot Smith (whose song “Needle in the Hay” is used to great effect in The Royal Tenenbaums) made raw and sad music. Iggy and Stooges—whose song “Search and Destroy” scores the major action sequence of The Life Aquatic—made raw and powerful music. Art can be a vent. But a person can’t live life in the nude.

In the 2002 documentary Gigantic, John Flansburgh of They Might Be Giants says he’s never wanted to “publicly cry” with his music. The band’s lyrics are dark, paranoid, and depressive—my favorite is a breakup song that includes the line “I’m going to die if you touch me one more time, but I guess that I’m going to die no matter what”—but the music is upbeat new-wave pop. Played any other way, the songs would be dirges. They would wallow. Wallowing has it’s place, but some feelings are too heavy to wallow in, they’re too dark to look directly at. They need a more inviting approach.

I should say here that this grudge against “quirky” is partially personal. My own writing has been described that way. Pieces I’ve written on hillbilly-themed television shows or the history of eating squirrel have been called “quirky” as a compliment. Though I wonder if the complimenters read them. These stories were, respectively, about a conservative takeover of television as a backlash to the civil rights movement and about stereotypes of poverty in midcentury America. Should I have underlined the point more? If I had, would anyone have read them?

What’s the alternative to artifice? Avoiding whimsy, detachment, or stylization isn’t just publicly crying, it’s limiting. There are a lot of tools an artist can use. There’s no one definitive way to deliver a message or to make a movie, just as there’s no definitive way to live your life or feel your own emotions.

To critique Anderson for his style is to suggest that he should make movies that look different. Which is to say he should make movies that look more like a conventional filmmaker’s view of movies. In truth, Anderson’s films are no more stylized than Quentin Tarantino’s, but because Tarantino works in a different palate (call it realist, call it violent, call it knock-off exploitation, call it traditionally masculine, or choose any other descriptor/compliment/detraction to fit your taste) he’s less often subject to the same critique.

To argue that Anderson, or any artist, is nothing more than a replicable style raises the question of why everybody else isn’t replicating it. If it’s so easy, so simply reduced to something anyone with a smartphone and some software filters can do, why is Anderson’s style still distinctively his? Attempts to do something similar—like Napoleon Dynamite or The Brothers Bloom—went the way of 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag, Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead, and the other talky, violent pictures that followed in Pulp Fiction’s wake. There is something that makes the original into a classic (cult or otherwise) and the copies into also-rans. It’s something that can’t be dismissed. It’s a difference between the viewer who is attempting to outsmart the work and a work that doesn’t exist to be outsmarted.

Sometimes the work may not exist fully to be understood. This is one message I took away from “Asteroid City.” An actor in the play-within-a-play can’t understand why his character burns his hand. The writer who wrote the script doesn’t know either. He stops to question, then he goes on. We won’t always understand why we do what we do. Our own emotions confuse us. But we have to accept that this is part of being alive. And sometimes we have to pretend to do something else.