Stranger Things Was an Ode to the Melancholy Children's Media of the '80s

The shift from introspection to action in Season 5 took away some of the show's unsettling power

When we are initially introduced to Eleven in the first season of Stranger Things, we meet a child who is terrified. She walks barefoot in the woods in a torn hospital gown. She breaks into the kitchen of a diner where she finds a basket of fries that she shovels into her mouth with both hands. The first grown-up that Eleven meets provides food but also calls child protective services, a dangerous predicament for El, who is trying to escape.

In these early episodes, we learn that it’s mostly well-intentioned adults who are under the illusion that you can trust authority. The kids understand there is only one chance for real safety: finding your friends.

One of the triumphs of the early seasons of Stranger Things is its commitment to presenting childhood as equal parts tender and terrifying, a sentiment common in the ‘80s media the show emulates. Children’s narratives in the late twentieth century embraced grittiness: characters, often parent figures, died. Sometimes children did too. The moral lessons in complex children’s tales like E.T. The Extra Terrestrial, The NeverEnding Story, The Land Before Time, and The Secret of NIMH are tenderhearted, but also haunting and sad.

I think one of the reasons that Stranger Things struck a chord with a wide audience was how well it captured this honest and authentic look at childhood, a mood that seems in direct contrast with today’s increasingly chipper children’s media. I don’t mean to suggest that upbeat programs with clear moral messages are without merit: the brand of emotionally resonant tearjerkers that Pixar and Disney regularly produce are often insightful and genuinely moving. But they also portray a sanitized vision of childhood, less wild, less complex, and maybe even less true.

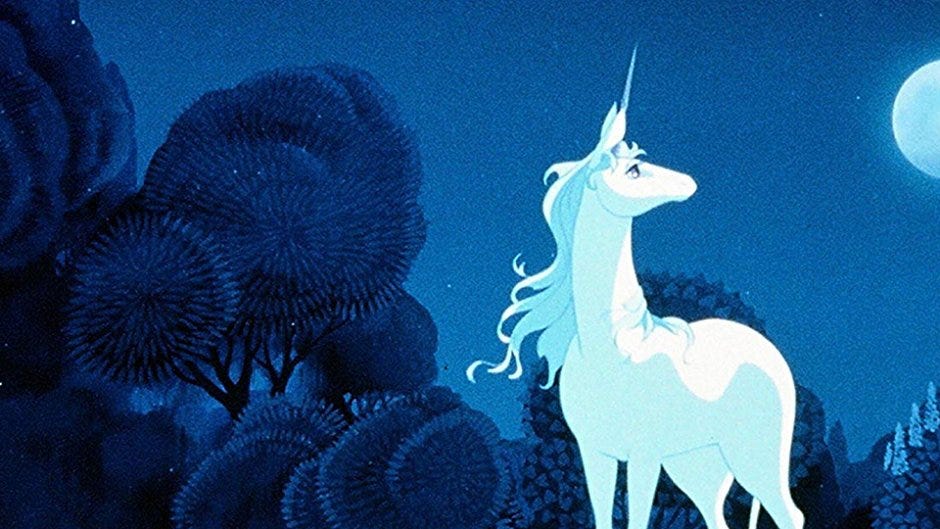

When I think about my own childhood, I remember finding discomforting narratives captivating. Stories like Where the Red Fern Grows, The Giver, and The Last Unicorn resonated because they didn’t feel like they talked down to me. Instead, they offered an opportunity to confront challenging emotions in a safe imaginative space. Like the best classic fairy tales, these stories resonate because they show us the real, imperfect world that exists under the veil of fantasy.

In early seasons of Stranger Things, viewers are welcomed into a similar emotional landscape, where we are confronted by the monsters from the Upside Down, as well as an array of real-world problems ranging from schoolyard bullies and absent fathers to the frightening unethical scientific experiments that El and many other captive children are desperately trying to escape.

In more recent seasons of Stranger Things, the tone shifted from introspection to action. The result is a show that eschews the heart of the ‘80s media it strove to emulate, embracing a 21st century superhero universe instead. There were more characters, more fight sequences, more big bad villains, and more speeches about good triumphing over evil. One of the biggest missteps was shifting away from the main cast (who, in fairness, were no longer children by the time the final season was in full swing) to a bunch of kidnapped children we knew so little about that they seemed more like the idea of children than actual characters.

These new children irritated me because the more time we spent with them, the less we spent with our original protagonists, especially Eleven, a character who I always felt was the heart of the series. From the start she was unique: tiny, feminine, odd, with halting speech patterns and a love of Eggo Waffles. Season 5 often flattened El, reducing her to her trauma. But El was a beloved character precisely because she was more than her history. El was brave, kind, and funny. In the end, she was willing to sacrifice everything to protect her friends.

We don’t hear Eleven’s voice in the end. Her story is taken over by Mike, as he weaves a tale of why he believes she ultimately survived. It’s a touching tribute as well as an appropriate end to the game he and his friends have been playing since childhood. We watch as our heroes, now young adults, give up their beloved basement for a younger generation. In these final moments, Stranger Things returns to the ‘80s media that inspired it, offering a satisfyingly unsettling moral: that nostalgia comes as much from willfully forgetting the past as it does from remembering it.

“These new children irritated me” — this line made me laugh. It’s been too long since Season 1 for me to finish the journey. Thanks for giving me a glimpse of the end.

The title "Together, Alone" captures perfectly what Stranger Things understood in its early seasons - that childhood often involves feeling simultaneously connected to friends yet isolated in facing certain truths that adults refuse to acknowledge. The idea that children had to find safety together because they were ultimately alone in understanding the real dangers resonates with that '80s media sensibility you describe so well.